Is it a good idea to get a degree?

A report in late 2016 by a think tank called the Intergenerational Foundation has looked in detail at the so-called graduate premium. This is the extra amount on average that graduates will earn over their working lives compared with those who do not go to university. They concluded that the size of this “premium” has often been hugely inflated by politicians and others and that this amounts to a case of mis-selling. So is university worth the investment?

The thing is that discussing a single, average figure is highly misleading because the returns to an individual vary so much by degree subject, university attended and the student’s personal background (such as whether they attended a state or private secondary school).

Lots of graduates end up doing jobs where they earn enough to have to make repayments on their student debt and this could effectively cancel out most of the uplift in salary they get from being a graduate in the first place. While the report definitely isn’t intended to put young people off from attending university, it should make young people and their parents weigh up very carefully the real value of the degree they are buying through their student loan repayments, particularly with the advent of higher and degree apprenticeships where trainees learn while they earn.

So is getting a degree a great idea or not?

Governments of every stripe in recent years have said a big “Yes!” to this and have pumped vast sums into expanding higher education. Universities have been turned into businesses that compete aggressively with each other to attract customers. When the costs started to balloon, tuition fees and student loans were brought in.

Faced with various half truths and the occasional downright lie from the government propaganda machine and the universities’ marketing departments, what are school leavers and their worried parents to do?

We have set out below the actual, real world reality as we see it. It should help you to weigh up the various options.

Over the next 20 years, the United Kingdom must create a society committed to learning throughout life. That commitment will be required from individuals, the state, employers and providers of education and training. Education is life enriching and desirable in its own right. It is fundamental to the achievement of an improved quality of life in the UK. (Dearing Report, 1997). There is a clear imperative for this.

The graduate labour market

Fifty years ago people with degrees were a tiny proportion of the total workforce. This was not seen as a problem as the number of jobs needing high level brain power were equally small in number. Things never stand still however and changes driven by increased global trade and rapid technological progress led to the demand for higher skills outstripping the supply coming out of the universities. In addition, the elitist nature of higher education was being challenged.

Over the intervening decades in response to these pressures there has been:

The thing is that discussing a single, average figure is highly misleading because the returns to an individual vary so much by degree subject, university attended and the student’s personal background (such as whether they attended a state or private secondary school).

Lots of graduates end up doing jobs where they earn enough to have to make repayments on their student debt and this could effectively cancel out most of the uplift in salary they get from being a graduate in the first place. While the report definitely isn’t intended to put young people off from attending university, it should make young people and their parents weigh up very carefully the real value of the degree they are buying through their student loan repayments, particularly with the advent of higher and degree apprenticeships where trainees learn while they earn.

So is getting a degree a great idea or not?

Governments of every stripe in recent years have said a big “Yes!” to this and have pumped vast sums into expanding higher education. Universities have been turned into businesses that compete aggressively with each other to attract customers. When the costs started to balloon, tuition fees and student loans were brought in.

Faced with various half truths and the occasional downright lie from the government propaganda machine and the universities’ marketing departments, what are school leavers and their worried parents to do?

We have set out below the actual, real world reality as we see it. It should help you to weigh up the various options.

Over the next 20 years, the United Kingdom must create a society committed to learning throughout life. That commitment will be required from individuals, the state, employers and providers of education and training. Education is life enriching and desirable in its own right. It is fundamental to the achievement of an improved quality of life in the UK. (Dearing Report, 1997). There is a clear imperative for this.

The graduate labour market

Fifty years ago people with degrees were a tiny proportion of the total workforce. This was not seen as a problem as the number of jobs needing high level brain power were equally small in number. Things never stand still however and changes driven by increased global trade and rapid technological progress led to the demand for higher skills outstripping the supply coming out of the universities. In addition, the elitist nature of higher education was being challenged.

Over the intervening decades in response to these pressures there has been:

- an expansion of higher education – Government grants were provided to enable students from middling and low income families to go to university. A positive outcome from this was a partial breaking down in social class hierarchy and greater social mobility.

- a reduction in the academic grades needed to get onto a degree course (for some subjects at less popular universities)

- conversely, for some courses at elite institutions such as the Russell Group of universities, a steady increase in the A level grades required due to the increased demand for places

- an increase in numbers of students staying on to take A levels

- the invention of vocational courses which also took two years of full time study and were classed as equivalent to A levels. This resulted in a big increase in the student population of FE colleges

- an erosion of quality (at least for some students) with increased student-tutor ratios, reduction in the use of small group tutorials and so on

- an explosion of new degree subjects with many of these having (or claiming to have) a job-related element (so called vocational degrees)

- a shift towards degree entry for occupations which used to accept young trainees with A levels or their vocational equivalents

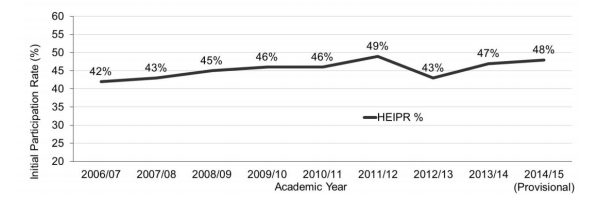

In 1950, just 3.4 per cent of young people went to university. Nowadays almost 40% do so. Successive government have encouraged and provided the funding for this expansion. Increasing cost has led to the burden being shifted to the student via the introduction of tuition fees so that today students provide about 60% of the cost of higher education with the remainder paid by the government. In fact, England has the highest tuition fees in the world, it seems.

These dramatic changes have led to a great debate between those who worry about the quality of teaching and learning falling as student numbers increase and those who see huge benefits for society and the economy and believe that further expansion is necessary. The introduction of the annual Teaching Excellence Framework league tables, where universities are ranked on their teaching, is an attempt to counter this.

Then there is concern that big student debts will lead to the improvement in social mobility going backwards. A further worry (expressed recently by the CIPD which represents personnel professionals) is that it is simplistic to expect that the economy will magically somehow create the right number of extra high-skill jobs for all the extra graduates coming out of universities. They say that we have already arrived at a point where a significant number of new graduates each year struggle to find employment that matches their aspirations.

The crucial thing to understand here is that this problem is not spread evenly across all universities and all subject areas. Graduates from certain popular, higher status universities are (on average) more likely to find suitable employment and graduates from certain subject areas also have better employment prospects, including some students from lower status institutions.

These dramatic changes have led to a great debate between those who worry about the quality of teaching and learning falling as student numbers increase and those who see huge benefits for society and the economy and believe that further expansion is necessary. The introduction of the annual Teaching Excellence Framework league tables, where universities are ranked on their teaching, is an attempt to counter this.

Then there is concern that big student debts will lead to the improvement in social mobility going backwards. A further worry (expressed recently by the CIPD which represents personnel professionals) is that it is simplistic to expect that the economy will magically somehow create the right number of extra high-skill jobs for all the extra graduates coming out of universities. They say that we have already arrived at a point where a significant number of new graduates each year struggle to find employment that matches their aspirations.

The crucial thing to understand here is that this problem is not spread evenly across all universities and all subject areas. Graduates from certain popular, higher status universities are (on average) more likely to find suitable employment and graduates from certain subject areas also have better employment prospects, including some students from lower status institutions.

Subjects with best employment prospects

- Education

- Science

- Mathematics/Statistics

- Law

- Medicine/Dentistry

- Subjects Allied to Medicine (e.g. biomedical science, physiotherapy. occupational therapy, nursing, pharmacology, optometry)

- Veterinary Science

- Business Studies/Management

- Marketing

- Economics

- Accounting and Finance

- Built Environment (architecture, construction, planning)

- Engineering

- Computer Science

On the job training.

In the old days, an apprenticeship was a much admired and highly desirable thing for many school leavers. Apprenticeships were a long term commitment between employer and young employee with some lasting for as much as five years. They were confined to manual trades that required lengthy training and highly developed skills. Some employers still provide this type of training with reasonable pay going up in steps to the full adult rate but again successive governments have meddled in things and reduced the standing of apprenticeships by watering down the quality of training while vastly increasing the number of occupations where it is possible to undertake one of the new-style, modern apprenticeships.

In the old days, an apprenticeship was a much admired and highly desirable thing for many school leavers. Apprenticeships were a long term commitment between employer and young employee with some lasting for as much as five years. They were confined to manual trades that required lengthy training and highly developed skills. Some employers still provide this type of training with reasonable pay going up in steps to the full adult rate but again successive governments have meddled in things and reduced the standing of apprenticeships by watering down the quality of training while vastly increasing the number of occupations where it is possible to undertake one of the new-style, modern apprenticeships.

The government recently felt obliged to insist on all apprenticeships lasting at least twelve months which shows that, in some sectors of the economy, the new style apprenticeships are a pale imitation of the more traditional kind. Employers are free to pay their apprentices what they like, subject to a statutory minimum, and nowadays pay rates vary hugely across the range of apprenticeships. It is a fact however that many thousands of apprentices on the shorter, lower quality schemes are paid a pitifully low wage.

All of these developments are part of deliberate policies to deregulate the workplace and create a flexible labour market which means that company profits are maximised while the rewards for employees are pushed as low as possible.

As with the world of higher education it is very important to be aware of the big variations in apprenticeships so that a well informed decision can be made about whether to go for this option or not. As well as pay rates and the length and quality of the training on offer there are big differences in the standard and desirability of the qualification that apprentices gain.

For example, it is not unheard of for employers to recruit youngsters with level 3 qualifications from school or college (such as A levels) and then have them working towards a vocational qualification (such as an NVQ) which is at level 2. Level 2 qualifications are at quite a low standard (roughly equivalent to 5 “good” GCSEs) and thus do not add much to the holder’s career prospects.

All of these developments are part of deliberate policies to deregulate the workplace and create a flexible labour market which means that company profits are maximised while the rewards for employees are pushed as low as possible.

As with the world of higher education it is very important to be aware of the big variations in apprenticeships so that a well informed decision can be made about whether to go for this option or not. As well as pay rates and the length and quality of the training on offer there are big differences in the standard and desirability of the qualification that apprentices gain.

For example, it is not unheard of for employers to recruit youngsters with level 3 qualifications from school or college (such as A levels) and then have them working towards a vocational qualification (such as an NVQ) which is at level 2. Level 2 qualifications are at quite a low standard (roughly equivalent to 5 “good” GCSEs) and thus do not add much to the holder’s career prospects.

Of course, the old adage that beggars can’t be choosers still applies and many young people make a pragmatic decision to enter these programmes as a way to gain experience and get that first foot hold in the world of work. It is also true that there are many good quality apprenticeships to be had which do not amount to exploitation and in fact provide an excellent start in working life for young people who prefer to learn by doing and not out of books!

Another important point to realise is that you don’t have to start an apprenticeship straight after GCSEs. Many students start after doing further study in sixth form or college. Bear in mind though that it can be harder to get accepted (because of the way apprenticeships are funded) once you reach the age of 19.

High Level Apprenticeships

There have always been employers who like to recruit bright school leavers at 18 or 19 who have done well in their A levels or Diploma and put them through their own in-house training programme. The picture has become a bit more complex with some companies deciding to opt instead for the government supported higher apprenticeship which leads to vocational qualifications at levels 4 and 5. An even more recent development is that work is now under way to develop new degree apprenticeships which will allow trainees to gain a degree while working and completely sidestep the problem of student debt.

Degree Apprenticeships

The recent introduction of Degree Apprenticeships launched in 2015, provides a different way of getting a degree by in particular, however may well have an impact on salaries and help them to stay similar to graduate salaries due to competition for talent. Degree Apprenticeships are co-designed between employers, universities and professional bodies and enable participants to get a degree while working. The big differences in taking this approach are that there are no fees for the student so they don’t accumulate the normal debt associated with degrees and in fact earn reasonably well during their training, depending on the sector and employer. Equally, they don’t live at university so won’t have university residential fees to pay either. This type of training approach is still very new to the sector and as a result, opportunities are not yet massive in number so may be harder to get due to their appeal, given that they include a real job from the start!

They will lose out on the experience of being a conventional student, but if their opportunity is away from home, they will gain similar skills, though possibly in a less supported way than universities offer and you may need to support them financially for a while. And then, there’s the challenge of balancing starting in the work place with learning and this may not be ideal if your teen is not very robust, particularly if they are living away from home for the first time.

Well ~ is it a good idea or not?!

Would you believe it – the answer is “yes” and “no”!

Some of the young people who currently choose to enter higher education would have better career prospects if they were to undertake a school leaver programme or apprenticeships and the arrival of degree apprenticeships certainly muddies the water in this regard.

The much increased numbers of graduates joining the labour market each year means that there are more applicants for each high-skill vacancy and therefore a greater risk of failing to find suitable employment. Obviously, this is a generalised statement. The jobs and graduates are not spread evenly around the country and this will make for variations in this competitive pressure.

Then there is the issue of the often mentioned mismatch between the vocational courses students choose at university and the need for new recruits in particular industries and occupations. Students who are keen to increase their chances of finding good employment might decide to choose from degree courses relevant to shortage occupations, though this does not mean necessarily that they will gain real satisfaction and success if they are not really motivated by the context. This highly instrumental approach can be viewed as using their student loan money to “purchase” an entry ticket to a secure, well paid job. Scientific, engineering and maths related courses fall into this category as do many IT courses.

The school leavers who face the hardest choice are those intelligent, hard working youngsters who (for various reasons) are not expected to get mostly A*/A /B grades at GCSE or 3 B+ grades at A level. The demanding nature of academic work at A level and degree level means that these students may drop out part way through A levels or a degree. If they complete the course they may gain a low grade which will put them at a severe disadvantage when competing for graduate entry jobs.

Such young people should at least ask the question “Will this really be worth the investment in effort, time and money and will it help take me in the career direction that I want to go in, or is there a better way to get there?”

The recent introduction of Degree Apprenticeships launched in 2015, provides a different way of getting a degree by in particular, however may well have an impact on salaries and help them to stay similar to graduate salaries due to competition for talent. Degree Apprenticeships are co-designed between employers, universities and professional bodies and enable participants to get a degree while working. The big differences in taking this approach are that there are no fees for the student so they don’t accumulate the normal debt associated with degrees and in fact earn reasonably well during their training, depending on the sector and employer. Equally, they don’t live at university so won’t have university residential fees to pay either. This type of training approach is still very new to the sector and as a result, opportunities are not yet massive in number so may be harder to get due to their appeal, given that they include a real job from the start!

They will lose out on the experience of being a conventional student, but if their opportunity is away from home, they will gain similar skills, though possibly in a less supported way than universities offer and you may need to support them financially for a while. And then, there’s the challenge of balancing starting in the work place with learning and this may not be ideal if your teen is not very robust, particularly if they are living away from home for the first time.

Well ~ is it a good idea or not?!

Would you believe it – the answer is “yes” and “no”!

Some of the young people who currently choose to enter higher education would have better career prospects if they were to undertake a school leaver programme or apprenticeships and the arrival of degree apprenticeships certainly muddies the water in this regard.

The much increased numbers of graduates joining the labour market each year means that there are more applicants for each high-skill vacancy and therefore a greater risk of failing to find suitable employment. Obviously, this is a generalised statement. The jobs and graduates are not spread evenly around the country and this will make for variations in this competitive pressure.

Then there is the issue of the often mentioned mismatch between the vocational courses students choose at university and the need for new recruits in particular industries and occupations. Students who are keen to increase their chances of finding good employment might decide to choose from degree courses relevant to shortage occupations, though this does not mean necessarily that they will gain real satisfaction and success if they are not really motivated by the context. This highly instrumental approach can be viewed as using their student loan money to “purchase” an entry ticket to a secure, well paid job. Scientific, engineering and maths related courses fall into this category as do many IT courses.

The school leavers who face the hardest choice are those intelligent, hard working youngsters who (for various reasons) are not expected to get mostly A*/A /B grades at GCSE or 3 B+ grades at A level. The demanding nature of academic work at A level and degree level means that these students may drop out part way through A levels or a degree. If they complete the course they may gain a low grade which will put them at a severe disadvantage when competing for graduate entry jobs.

Such young people should at least ask the question “Will this really be worth the investment in effort, time and money and will it help take me in the career direction that I want to go in, or is there a better way to get there?”